Alito issues statement on confrontation clause gun case

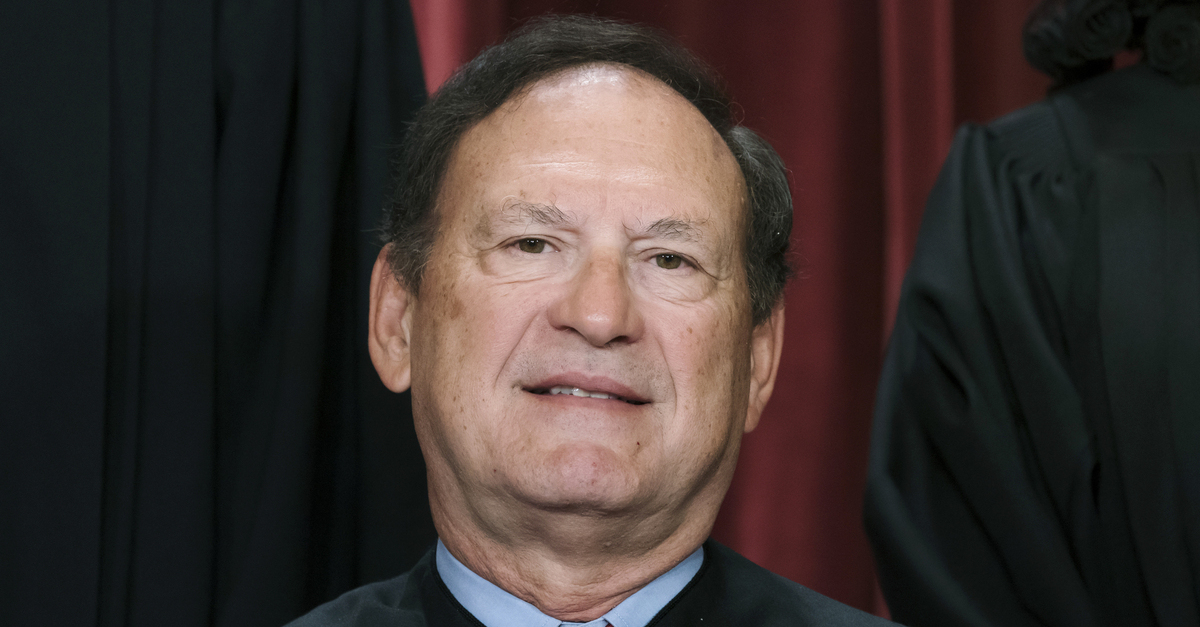

FILE – Associate Justice Samuel Alito joins other members of the Supreme Court as they pose for a new group portrait, Oct. 7, 2022, at the Supreme Court building in Washington. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

The Supreme Court declined to review the case of a New York man who was criminally convicted after a form listing his self-provided address was used against him as evidence at trial — and although Justice Samuel Alito agreed with the high court’s declination, he nonetheless issued a detailed statement encouraging his colleagues to reconsider what exactly the Constitution’s confrontation clause prohibits.

Cid Franklin and the basement gun

Police officers had been responding to a road rage incident that included a report of a firearm when they searched the basement of the home Cid Franklin shared with his son and stepmother, Grace Mapp. During the search, police found a gun in the basement closet, along with blankets, pillows, and other items belonging to both Franklin and Mapp. Franklin was subsequently arrested. While he waited for his arraignment in central booking, Franklin was interviewed by an employee of the Criminal Justice Agency (CJA), as is standard practice for New York City defendants.

CJA is a nonprofit organization funded by the city of New York that provides pretrial services for nearly all arrestees. CJA employees interview individuals arrested to determine whether they would be suitable for pretrial release, then record the answers in an official “Interview Report,” which is later given to the arraignment judge, the prosecutor, and defense counsel. The CJA employee assigned to each case independently verifies the information given by arrestees about their community ties, warrant history, length of time at present address, employment status, family support, education, and other relevant background information.

During Franklin’s CJA interview, the CJA employee recorded Franklin’s address as the basement of 117-48 168th Street, then verified the information with Mapp, referred to as Franklin’s “mother” on the form.

The gun that had been found had no DNA or fingerprints on it, and none of the witnesses who testified at trial provided direct proof that Franklin actually lived in the basement. However, over the objection of defense counsel, prosecutors used the CJA form as evidence that Franklin had dominion and control over the basement.

Ultimately, Franklin was convicted of one count of second-degree criminal possession of a weapon.

Franklin’s appeal and the confrontation clause

On appeal, Franklin argued, among other things, that the CJA form was improperly admitted against him in violation of the confrontation clause. The New York courts disagreed with Franklin and held that the Sixth Amendment only bars the use of “testimonial” out-of-court statements — those that were created for the primary purpose of serving as trial testimony. Because the CJA form had an entirely different and “administrative” purpose — and not testimonial — its admission and use against Franklin was found not to have violated the confrontation clause.

Under the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, “[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right … to be confronted with the witnesses against [them].”

Generally, the interpretation of the scope of the confrontation clause was set out in the 2004 ruling in Crawford v. Washington, in which the Supreme Court ruled that “testimonial” statements from witnesses not subject to cross-examination at trial are inadmissible against a criminal defendant.

The justices decline to overturn New York’s ruling

The justices denied Franklin’s petition for certiorari. Alito, however, appears to think it is time to retool Crawford’s rule and revamp the manner in which courts consider what is actually covered by the Confrontation Clause.

Under Crawford, Alito said, not only have the results have been “unpredictable and inconsistent,” but they have also conflicted with “relevant common law rules at the time of the adoption of the Sixth Amendment[.]”

This problem, said Alito, “continues to confound courts, attorneys, and commentators.” The justice argued in a four-page statement on the Court’s denial of certiorari that Crawford’s rule prohibiting the use of “testimonial statements” had the effect of creating a meaning of the term “witness” that is “radically different” from what was meant in other parts of the Constitution.

Alito concluded that “the current state of our Confrontation Clause jurisprudence is unstable and badly in need of repair,” and argued that any efforts to fix the problem should not be limited by a requirement that they stay within the confines of the Crawford ruling — which Alito called “a fundamentally unsound structure.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch penned his own seven-page statement on the Franklin case in which he largely agreed with Alito. Gorsuch also lamented the inconsistent results reached by applying the Crawford test. Gorsuch noted that the Supreme Court never even tried to justify the Crawford test on the basis of the Sixth Amendment’s original meaning and argued that judges should not be concerned with what a document’s primary purpose was at the time of creation — but rather, whether “the government seeks to use a witness’s statement at trial against a defendant in lieu of live testimony.”

The justices’ denial of certiorari in the Franklin case means that his individual conviction will not be overturned on confrontation clause grounds and for the time being, Crawford will remain in place as the applicable test.

You can read the justices’ full statements here.